Specialised Low Order Techniques Course – PCM’s MAT Kosovo, BODAC & ECS Special Projects

January 17, 2020

The MAT Kosovo EOD & ERW Training Establishment Supports Regional Health Authorities

March 23, 2020

Original Article by Xhorxhina Bami (Peja/Pec, BIRN) – balkaninsight.com – March 9, 2020

[Read the original article]

After the success of efforts to clear unexploded mines from the 1998-99 war, a training centre in Kosovo is teaching deminers to remove explosives in other conflict-ravaged countries around the world.

Yugoslav-era mines lie scattered across the ground in an area marked off with sticks. In the middle of the area, the remains of a dead animal can be seen.

To the left, another zone is marked as ‘contaminated’ with unexploded ordnance, although no mines are visible to the eye. Instead, they are covered by vegetation, even deadlier than if they were in plain sight.

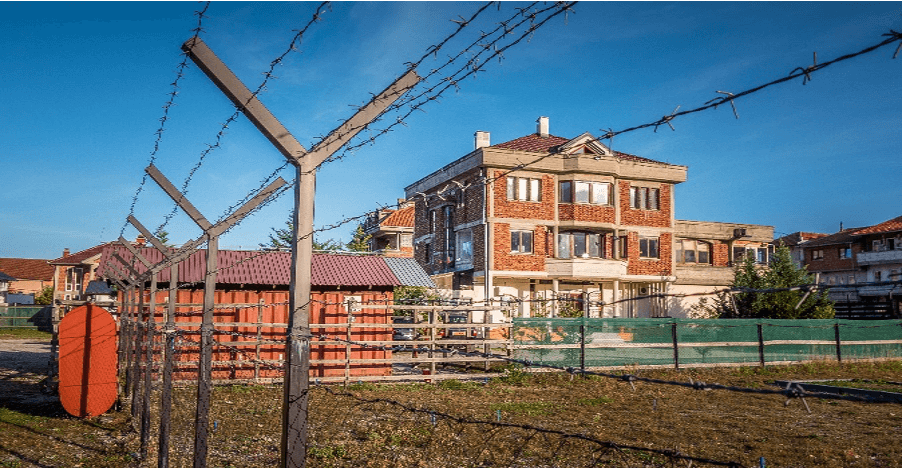

This is a mocked-up minefield at the MAT Kosovo training centre in the town of Peja/Pec, intended to simulate the kind of treacherous terrain that deminers will find when they are working in the field. The only difference is that the mines here at the training centre have been deactivated.

Kosovo was widely contaminated with unexploded devices during the war in 1999, and until the UN declared it free from mines in 2001, the country was the epicentre of humanitarian mine action.

The rapid success in clearing Kosovo of mines has helped to establish its reputation as a good location for training.

“Would you be trained in mine-clearing in Geneva or in a country that has a successful background in establishing safety on the ground?” asked Mohammad Hassan from Syria, one of the trainees at MAT Kosovo.

MAT Kosovo is a sister organisation of Praedium Consulting Malta, a risk management company dealing with the clearing of unexploded ordnance, and started out as a charitable organisation called the Mine Awareness Trust.

In 2010, it established its training centre in Peja/Pec and has since taught thousands of people mine disposal techniques and explosives risk management skills.

Over the past four years, around 500 people have been certified in the courses held in Kosovo, and some 650 more have been trained on the ground amid the conflict in Syria.

Ben Remfrey, the explosive remnants of war risk manager at Praedium Consulting Malta and MAT Kosovo, is a former British soldier who first came to Kosovo in 1999 as a NATO consultant.

Remfrey told BIRN that the UN’s post-war mine-clearing operation in Kosovo included “minefields, the remnants of the bombs dropped by NATO during the bombing, abandoned ammunition, and confrontation lines where the KLA [Kosovo Liberation Army] and NATO were fighting against the Serbian paramilitary forces”.

After the war, Yugoslav maps of 600 minefields laid by the Yugoslav Army across Kosovo were available to the UN and NATO to aid the mine-clearing process. However, there were no records of mines laid by Serbian special police forces and paramilitaries or by the KLA.

Meanwhile, bombs dropped by NATO during its air raids had an estimated 10 to 20 per cent failure rate, creating further potential hazards from unexploded munitions.

Remfrey said that “while the people of Kosovo suffered greatly, the mine action programme was actually a good one”.

Nevertheless, since Kosovo was declared mine-free in 2001, around 100 people have been reported injured by blasts or during ordnance disposal training.

Hidden devices create post-conflict hazards

The instructors at MAT Kosovo lead the trainees as they practice using metal detectors to find concealed mines in a mocked-up minefield.

“Based on the signal that resonates from the metal detector, the students understand how it sounds when the ground is contaminated or not,” explained Remfrey.

In another part of the training centre, the instructors have buried the remnants of a bomb two metres below the ground. To find it, the trainees use another tool, a locator. Locators have more reach than metal detectors and can detect materials buried deep in the ground that are not natural to their surroundings.

“We also use ground-penetrating radar for non-metallic components, and our dog, Sunny,” Remfrey added.

Artur Tigani, the head instructor at MAT Kosovo, served in the Yugoslav People’s Army from 1982 to 1984 and has been deployed in civilian mine-clearing missions in Kosovo, Sri Lanka, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Kenya, as well as doing training in explosives clearance in Syria and Iraq.

Tigani explained how a couple of years after a conflict, vegetation grows over the mines, concealing them from view.

After this has happened, “injured animals and humans are usually the indicators of suspicion for a mine-contaminated area”, he said.

One of the most common scenarios that alert people to the presence of mines is when cattle run into a contaminated area and shepherds run after them and accidentally activate a concealed mine, he added.

Military and civilian mine-clearing

While civilian mine clearance aims to make areas safe to live in, MAT Kosovo head instructor Artur Tigani explained that soldiers are not trained to fully demine contaminated areas, but focus instead on clearing paths from one place to another to achieve the army’s strategic goals.

Mine clearance activities by humanitarian relief organisations usually happen in so-called ‘permissive’ environments, which means that they can operate without fearing random attacks, or in ‘semi-permissive’ environments.

Post-war Kosovo was a permissive environment, while Syria and Iraq are currently semi-permissive environments. Mine clearance in conflict zones like these usually happens in areas which are no longer frontlines and is carried out during a truce.

However, while the danger of unexpected attacks or the restarting of the conflict persists, more robust security measures need to be put in place.

Success and setbacks in Syria

MAT Kosovo has also established programmes to train people to clear improvised explosive devices, which are often used by armed militant groups.

Tigani showed some examples of home-made devices to BIRN and described how some of them incorporate buttons from computer keyboards which, when stepped on, activate the explosives.

“We train students on how to detect, locate and destroy such homemade explosive devices as well,” he said.

MAT Kosovo’s trainers were working during the conflict in Syria even before the defeat of the so-called Islamic State’s forces.

“We have also trained 650 Kurds in Syria a little before the fall of ISIS. Artur and a part of the training team were in Syria for 21 months. We were working there while ISIS was still operating,” said Remfrey.

While in Syria, MAT Kosovo and other humanitarian relief organisations managed to make the environment safe for civilians to go back to their homes. The initial phase of mine clearance – making safe essential service facilities like electricity plants and water supply sources, schools, and hospitals – was a success, Tigani said: “Many displaced Syrians returned.”

However, as the security situation deteriorated again, “they abandoned their houses once again”, he added with regret.

He argued that the time that he and the other MAT Kosovo experts spent working in Syria was worthwhile even though they ultimately had to pull out due to the worsening situation on the ground.

“We managed to clear the environment of very dangerous devices. However, from a semi-permissive environment, it soon turned into a non-permissive one. After 21 months there, we had to withdraw,” he said.